Juan Haro

THE SOUL OF THE ARTIST. STUDIO SHOTTING BY

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JEAN MARIE DEL MORAL @JEANMARIEDELMORAL WORDS BY ALVAR HARO

@ALVARHAROARTIST MADRID. SPAIN.

Intemperie.

My father learned to carve stone when he was just a child, under the sun, with the marble workers and stonemasons of Montjuic in Barcelona. He quickly absorbed the techniques, honing his skills to master craftsmanship that had remained unchanged for millennia, before machines became prevalent. Even today, in his workshop, you’ll find cardboard boxes bearing the logos of some Parisian trades, filled with chisels, rasps, and iron mallets that have been deformed by countless blows. These attest to his preference for ancestral methods.

He always worked with his blocks outdoors, sometimes under an improvised roof of sheet metal and wood. The scorching sun, the wind, the rain, and even the ice seemed to fuel his fervor with the mallet. With incredible dexterity, he engaged in a perfect symbiosis with the material, skillfully chiseling away enormous stone slabs in a flurry of accurate and surprisingly swift blows. It was a spectacle to behold. He believed in removing only what was extraneous, uncovering the figure contained within, akin to Michelangelo’s approach. His conception of sculpture was that of the carver, the one who subtracts material, the one who synthesizes until the sculpture becomes that which lacks nothing, as if only the essential remained after rolling down the slope of a mountain.

The direct sun defined the volumes, unveiling the full chromatic range of the material. In this radiant environment, he felt free and connected with the ancient sculptures he admired, such as those from Egypt, Ur, and Mesopotamia. He favored hard stones like diorite or basalt. And the Romanesque. A journey pedaled through Catalonia and later in France in a Citroën 2CV. From Romanesque sculpture, he distilled part of his compositional concept: gathered and dense figures, subjected to the centripetal laws of the block and its internal rhythms, surfaces touching and describing its edges or boundaries… as well explained by Henri Focillon in his “Vie des formes”.

A formal refinement advocated by the avant- gardes, Modigliani, Brancusi, or Manolo Hugué, whom my father admired and couldn’t meet due to age but maintained a close and endearing friendship with his family, his widow Tototte and daughter Rosa, frequently visiting their farmhouse in Caldes de Montbui, where he learned from Manolo’s carvings and had the opportunity to see his early Picassos. On a barren hill near Cuevas del Almanzora, Almería, practically exposed to the elements, in a humble, meager, and isolated family farmhouse of laborers and shepherds, he was born on October 18, 1932. These lands scorched by the sun and wind, under an infinite blanket of stars, on grounds dotted with minerals and Punic or Argaric tombs, similar to the ones that had attracted the Belgian archaeologist Luis Siret decades before, and vast landscapes with distant horizons. I like to think that something of all this permeated him and came alive when he worked with stone. Those Catalan marble workshops still preserved in the 1940s the artisanal excellence that shone during the Modernist era and the preparation for the 1929 Universal Exhibition.

In addition to carving, he learned everything in those workshops, various trades that he perfected and adapted to his needs. It was there that he had his first contacts with the underground opposition to Franco’s regime, mainly of an anarchist nature. At night, in a boxing club, he would tense his muscles, sharpen his reflexes, and release his anger, especially social anger. He eagerly devoured all kinds of books, many of which were banned, from the library of his friend and neighbor, the writer Francisco Candel, the finest chronicler of that poor neighborhood in Zona Franca. He drew at the Llotja, in nocturnal cafes, and in the streets, frenetic teachers of life. He worked as an assistant to sculptors Viladomat, Clará, and Joan Miró, with whom he maintained a lifelong friendship. And he felt the need to escape as far as possible: to Morocco, Caracas, and the still art mecca, Paris.

Nine years in Paris, the city of the Louvre, avant- gardes, and the entire history of modern art. It was a city of international galleries and where the traditional bal musette was overshadowed by the likes of La Gréco and Brassens. In Paris, he contrasted his youthful intuitions about Zadkine, Lipchitz, and Laurens, admired the refinement of Brancusi, studied closely the works of Michelangelo, Houdon, Rodin, and the ancient Egyptian empire. He formed friendships with Giacometti, Clavé, Alain Resnais, and Semprún. He founded and directed the Association of Spanish Artists in Paris, promoting iconic editions such as “Asturias” in Cahiers d’Art with the collaboration of Picasso. It was in Paris where he met my mother, who came from the Republican exile in the USSR and Warsaw, and where I was born. He worked for a taxidermist, and we still have splendid notebooks filled with his exquisite drawings of animal skulls because he was an exceptional artist.

Above all, he experienced freedom and progress that did not exist in Spain at the time. We lived with great excitement in a 17 m2 apartment in Issy les Moulineaux, adorned with clever foldable furniture constructed by my father. It was a town in the suburbs with a communist town hall, a Norman church housing a Ribera painting, Matisse’s studio, and Pierrette Gargallo’s house, which my father frequented. Meudon, the house-studio of Rodin, was also nearby. My father’s studio was located in the courtyard of an Armenian tailor. Every night, he would hoist the sculpture he was working on over his shoulder and carry it up steep alleyways the apartment, ready to resume the process the next day.

The edges and facets of his initial stage, which were more “expressionist” phase gradually gave way to an emerging style of maturity, characterized by a more “rounded” and resolute form. This caught the attention of Jean Cassou, who awarded him the National Sculpture Prize from the Ville de St Denis. Upon leaving Paris for Madrid in 1967, something he occasionally regretted, he brought with him an unmistakable style, a vast intellectual wealth, and, as he used to say, the habit of listening to others and letting them speak. He was an intelligent, entertaining conversationalist with a naturally shared culture, unaffected and possessed a unique magnetism. Since his arrival in Madrid, he achieved rapid consecration, rising to the forefront of Spanish art and being recognized as one of the finest stone carvers the country has produced in the past century.

He captured the fervent attention of Spanish and foreign weeklies, critics, galleries, collectors, museums, and foundations. The Madrid of the 1960s and 1970s that I remember still retained the charm of a certain Solanesque bohemia, with its Ramonian flea market, rough wine taverns, and traditionalism. Coffee gatherings and impromptu encounters in art galleries were common, while a general yearning for political change permeated the air. By the mid-1980s, engrossed in creating large murals for institutions, he somewhat distanced himself from the art gallery scene, as a new generation of artists with different approaches emerged. However, he continued, as always, to carve in the open air, anchored to the earth like a child of the sun and the wind.

Shelter.

The summer of 1982 marked a turning point in the family’s life: we moved to live in the house my parents had just built, often with their own hands, fulfilling a long-held dream. A rationalist dwelling of simple geometry painted in light beige, surrounded by a narrow garden belt, with spaces to showcase the sculptures, as they only “materialize” with the right light, along with a spacious workshop with a high ceiling and north-facing windows, reminiscent of those in Paris. It was a project of my father and Manuel Gutiérrez Plaza, an architect who was a close friend and collector. Among other collaborations, they also worked together on the pantheon of the Ungría family in the Sacramental de San Isidro, inspired by ancient mastabas, considered the finest funerary building of the twentieth century in Madrid.

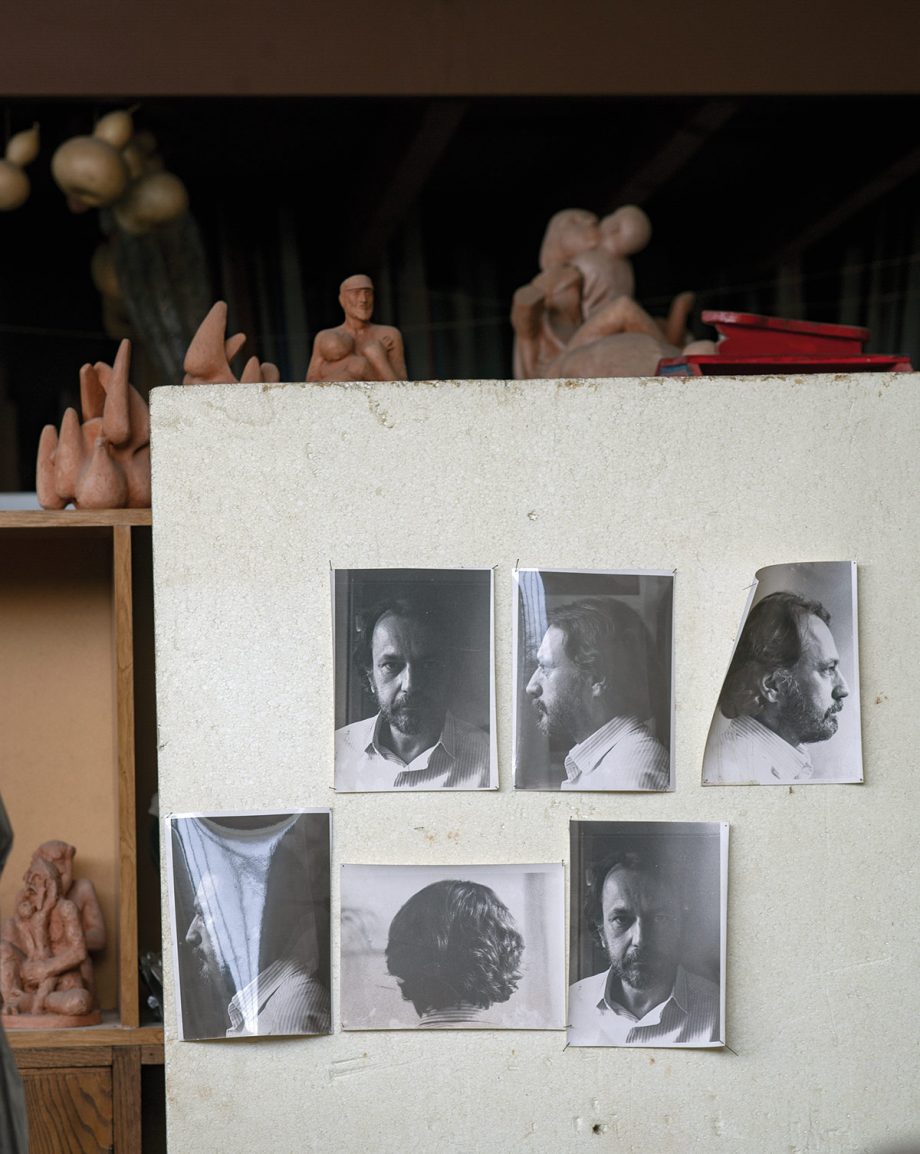

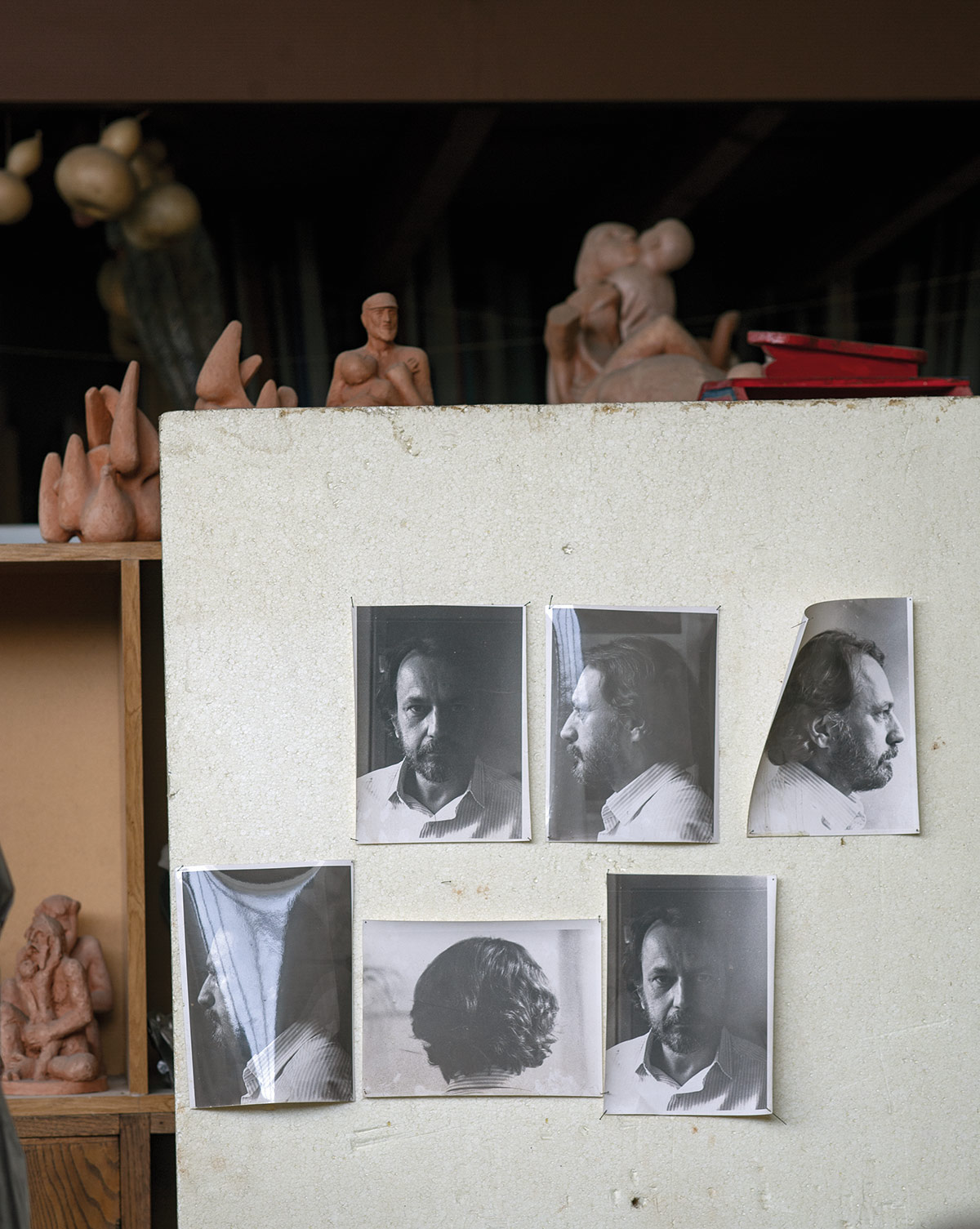

Finally, the first truly personal workshop, right at home, after a history of borrowed spaces, like the courtyard-storage of a marble worker in the Elipa neighborhood or a small basement without natural light in the center of Madrid. It amazes me to think of those precarious places receiving visits from the cream of Spanish art, such as Francesc Català Roca in Barcelona, who captured splendid shots of the works on- site (a cramped interior room of 6 m2), or the March family descending the treacherous and narrow stairs of the basement, not without risk. The north-facing orientation of the glass panel allows for minimal variation in light, except for brief lateral sun rays in summer.

In the early autumn of 1982, the workshop was nearly empty, with the scent of quinces from our young tree filling the air, and the light reminiscent of that in Holland and sometimes Paris. It was a special, elusive, and ever-changing light. During a weekend, my father and his brother, a welder, constructed a loft for graphic work with iron and wood, complete with a beautiful staircase for access and a railing adorned today with posters of González, Gargallo, Chillida, and his own works. From there, one can contemplate the workshop like a vast landscape inhabited by beings, peaks, and valleys. In the summer of 1982, while we were on the Acropolis of Athens for a symposium on Mediterranean sculpture, I discovered my vocation as an artist in an illuminating moment. It was like falling off a horse on the road to Damascus. After a month of traveling alone with my father, hopping from island to island through the vagaries of the Aegean Sea on boats of all shapes and sizes, I got to know him in depth as I had never imagined. He became my best friend forever.

My dedication to painting was not initially planned. I discreetly and gratefully occupied one end of the workshop, but with a dangerous tendency to expand, ultimately requiring the establishment of a constantly transgressed border between his territory and mine. With his guidance, that place became my school of art and life. For years, from sunrise to sunset, we worked side by side, engaging in dialogue from our respective corners, intertwining jokes with lessons of all kinds. We listened to the same music, breathed in the scents of cut wood, wet clay, plaster, and turpentine, always enjoying ourselves and laughing under the relentless rigor of Leonardo. Thus, the workshop, with its Dutch lighting and Parisian structure anchored in Madrid, occasionally took on a Florentine accent. Sweeping to think, in the morning. Tidying up at night to prepare for the next day’s work. Workshop discipline.

Today, it is a space of stratified accumulation from various eras, a ferment for new ideas. I excuse Bacon and Freud, cultivating their refined works amidst the silt of accumulation. Everything and nothing serves a purpose. A myriad of figurines dance on the shelves, reverberating at our passing, tinkling with a thousand stimuli, colours, and shapes. Remnants of projects, faded large drawings on the walls, the silk thread of an uninhabited cobweb high above, tables upon tables rendered unusable by papers (when one is full, another is added), containers and bottles velvety with light, their pearly veil of dust resembling Morandi’s still lifes. Pieces of wood trim and piles of sawdust surround a handheld miter saw, emitting the scent of carpentry. Easels, patinated or not, terracottas, occasional powerful figures breaking the rhythm, and countless details to delight in.

Small pieces from youth with Cubist echoes, sketches destined for stone carvings that will never be, a keychain from the Trieste transatlantic liner that took him to America, a tin toy monkey climber, notebooks with notes, drawings, and telephone numbers from a time before local area codes existed. Fossils of a life that I witnessed and yet still pulsate… As Jean Marie del Moral nostalgically told me, “Workshops like this no longer exist.” They were so personal yet deeply rooted in the finest tradition of the 20th century. For others, one is defined by what they do, but for oneself, it is what one dreams of or leaves undone, and that can be sensed in the workshop, a self-portrait in physical space. The artwork itself remains a small element within the general magma or cosmos, in this case, densely populated, much like Picasso’s La Californie or Brancusi’s studio, which ours, incidentally, shares similarities with—both with an invisible geometry imbued with meaning.

Flight.

Juan Haro was primarily interested in portraying the human being, often imbued with deep dramatism and a certain symbolic weight, depicting embraces, kisses, and loving or maternal interactions, as well as battles and death… He was also captivated by animals. One of his most renowned series is the collection of flying pigeons, stones that can usually rotate on themselves through a mechanism he invented anchored to the pedestal. Five days before his passing, we arranged some terracotta sketches from the series under a glass bell, to organize them a bit. “There, they can no longer fly,” he said, with a tone that foresaw the end, but he added that he had renewed eagerness to continue with the series. Always spirited and ready to spar with adversity. He disliked caged birds; as a child, he would release the ones his cousin caught from the hill to see them fly over the meadow of the Almanzora River.

The figures in the workshop also “fly” beyond the walls, transported to other places and skies by the ever-changing and magical light that filters through the glass. This translucent membrane blurs the boundary between inside and outside. While time seems to stand still within these walls, the song of the blackbird penetrates, marking the arrival of spring, and the wind rustling through the branches announces the end of summer. That is the magnetism of this place: an animated and interconnected stillness, supported by the layers of memories that continue to germinate in new works. With my father, it was a source of life, and now it serves me as a refuge, evoking past sensations and connecting me with his spirit and my own youthful dreams. It is my genetic card that reinforces my balance and what best defines us.

Alvar Haro. Madrid. April 2023.