Two tough guys. The Rasch Brothers

January 30, 2026. WOrds by Suso Barciela. Piece with artist magazine.

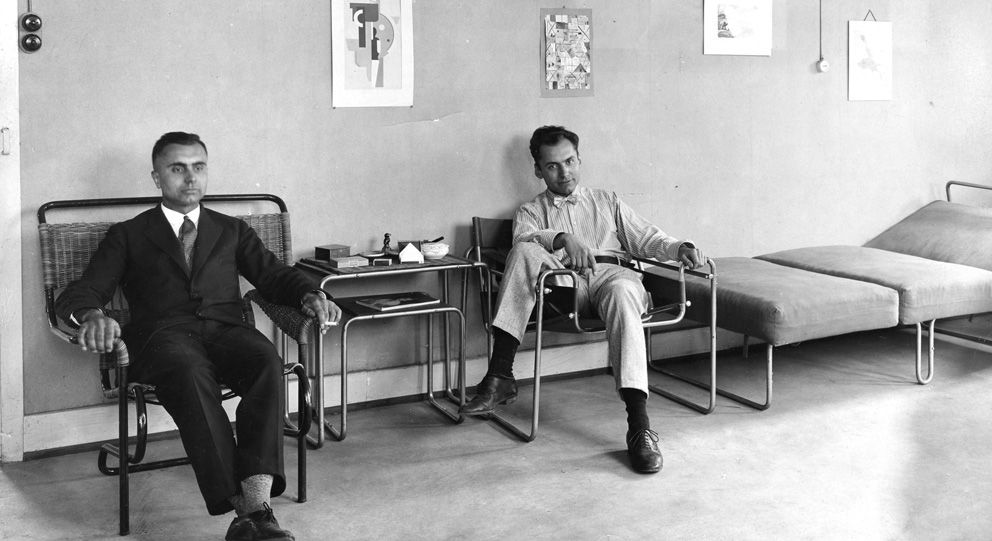

Two very brave figures of their time, who were not understood in their moment (they did not see any of their buildings realized) and who, to this day, are still difficult to fully grasp. They had a vision…

Heinz Rasch studied in 1916 at the School of Arts and Crafts in Bromberg, and from 1920 to 1923 studied architecture at the Technical Universities of Hanover and Stuttgart, and began to dedicate himself to the manufacture of lamps and wooden chairs. He combined this craft with his role as press officer for the Stuttgart building exhibition in 1924, and in 1926 he was in charge of editing the specialized magazine Die Baugilde (BDA). That same year, and until 1930, he and his brother Bodo Rasch (1903-1995) ran an architecture, furniture, and advertising office in Stuttgart.

In 1930, Rasch came to Wuppertal to carry out several new buildings for the chemist and paint manufacturer Kurt Herberts. His friendship with Willi Baumeister and Oskar Schlemmer (it must be said) helped him secure this opportunity, which he would not waste. As a result, he opened a «New Arts Study» in 1945 at Döppersberg, and it was there that he emerged as the organizer of many art exhibitions, becoming a key figure in the reconstruction of Wuppertal’s artistic life. Furthermore, Rasch was on the board of the museum and art association and was organized in the Association of German Architects.

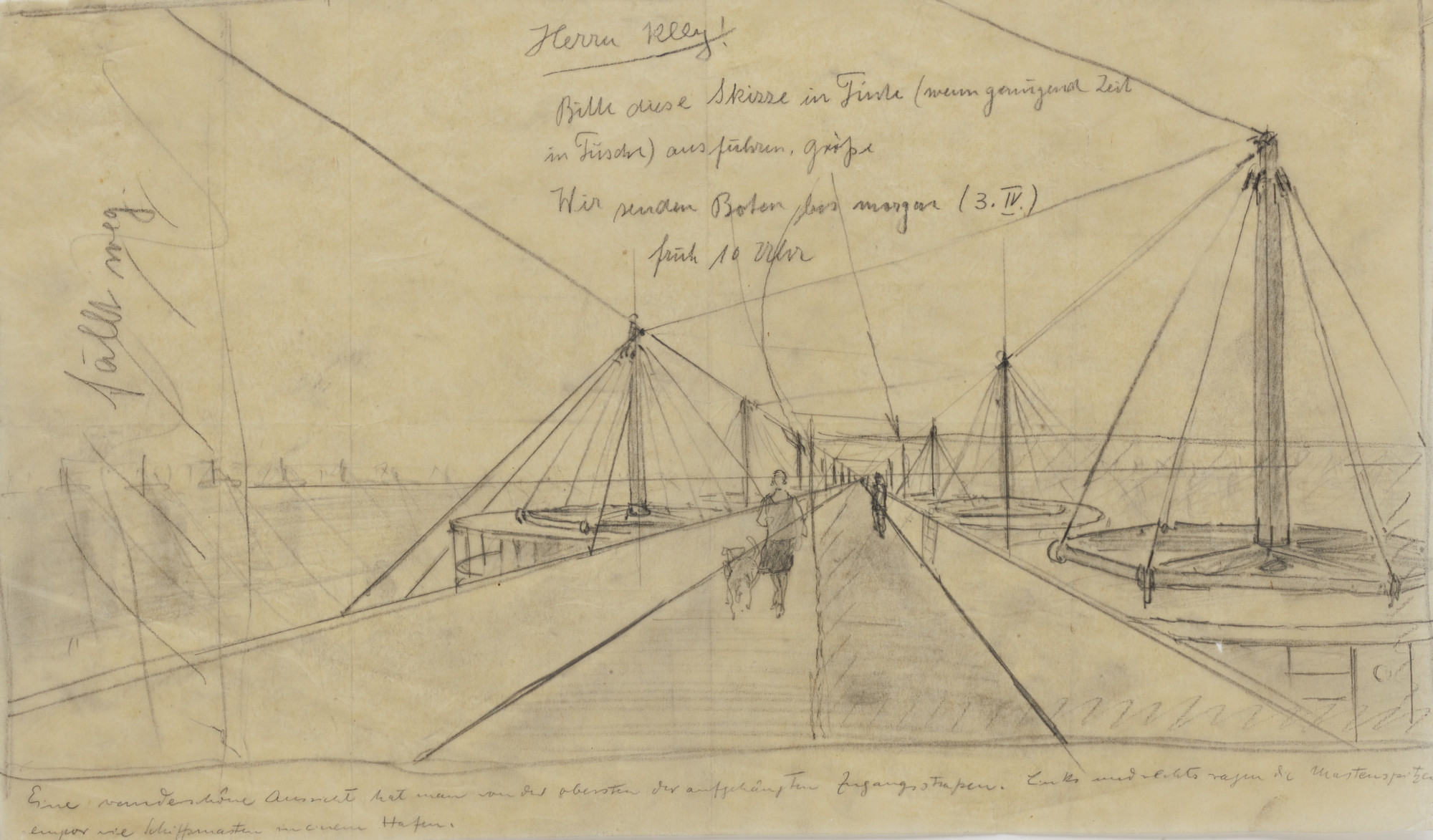

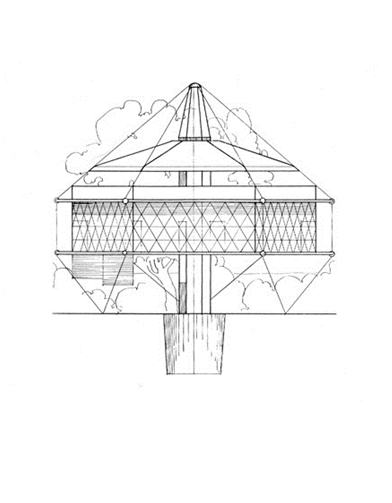

His construction principle, in which the building was suspended around steel pillars or a concrete core, is still used today.Through hard work, he evolved from a pioneer of a new idea to an executor of «construction industry functionalism.» This was the term coined by the founding director of the Deutsches Architekturmuseum, Heinrich Klotz, to describe a modernist practice that made its peace with minimal programs and did not concern itself with thoughtful designs or deeper questions about the meaning of architecture. Functionalism above all, in its purest form.

Heinz Rasch (1902 – 1996) studied architecture at the higher technical schools of Hanover and Stuttgart. He wanted to complete his studies with Paul Bonatz, author of the design for Stuttgart’s main train station, then under construction. With a studio project, Heinz Rasch initially found himself under the tutelage of another Stuttgart professor, Paul Schmitthenner. Rasch had proposed a «hillside arch for my idea of a villa on a slope.» It was an early example of organic architecture that Schmitthenner vehemently rejected, accusing Rasch of having an «unfocused mind.»

In an autobiographical article written in 1990, Rasch notes that this public humiliation at the university was «subconsciously present in all my designs» throughout his life. A terrible idea.This and other episodes from the life and work of the two designers are outlined and structured by Annette Ludwig in her precise and intelligent monograph on the «Architekten Brüder Heinz und Bodo Rasch,» published in 2009. The author documents how Heinz Rasch wrote almost daily to his girlfriend and later wife Jutta Kochanowski about life and work between 1926 and 1930, adding photos and small drawings.

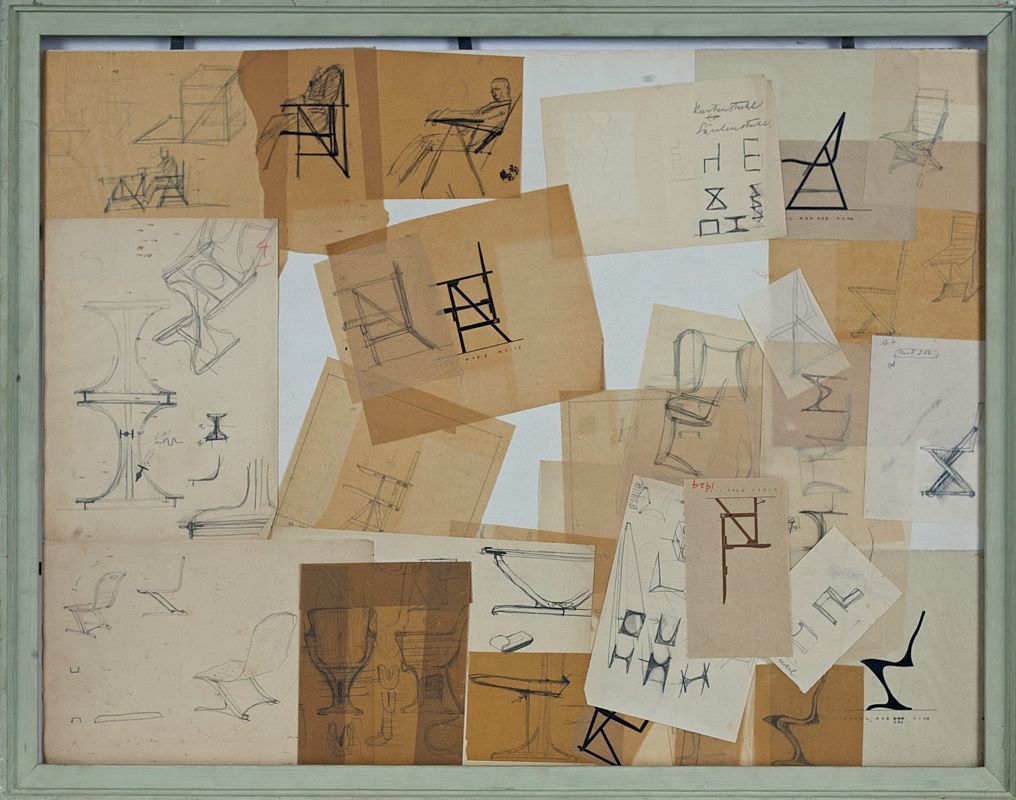

The correspondence also describes various successes and events, such as the visit of Mies van der Rohe, who finalized the plans for the Weissenhof estate in Rasch’s office, not forgetting reports on setbacks and financial difficulties.For his part, Bodo Rasch (1903 -1995) initially graduated as an agricultural engineer. During that time, he trained and worked for several cabinetmakers, acquiring knowledge of furniture design and manufacturing. From 1923 onward, he developed craft objects, and from 1924, he designed chairs. During this period, Heinz and Bodo collaborated sporadically. «Werkkunst Arche» and «Deutsche WA-Möbel-Gesellschaft» were the names of their first companies, which they quickly abandoned.

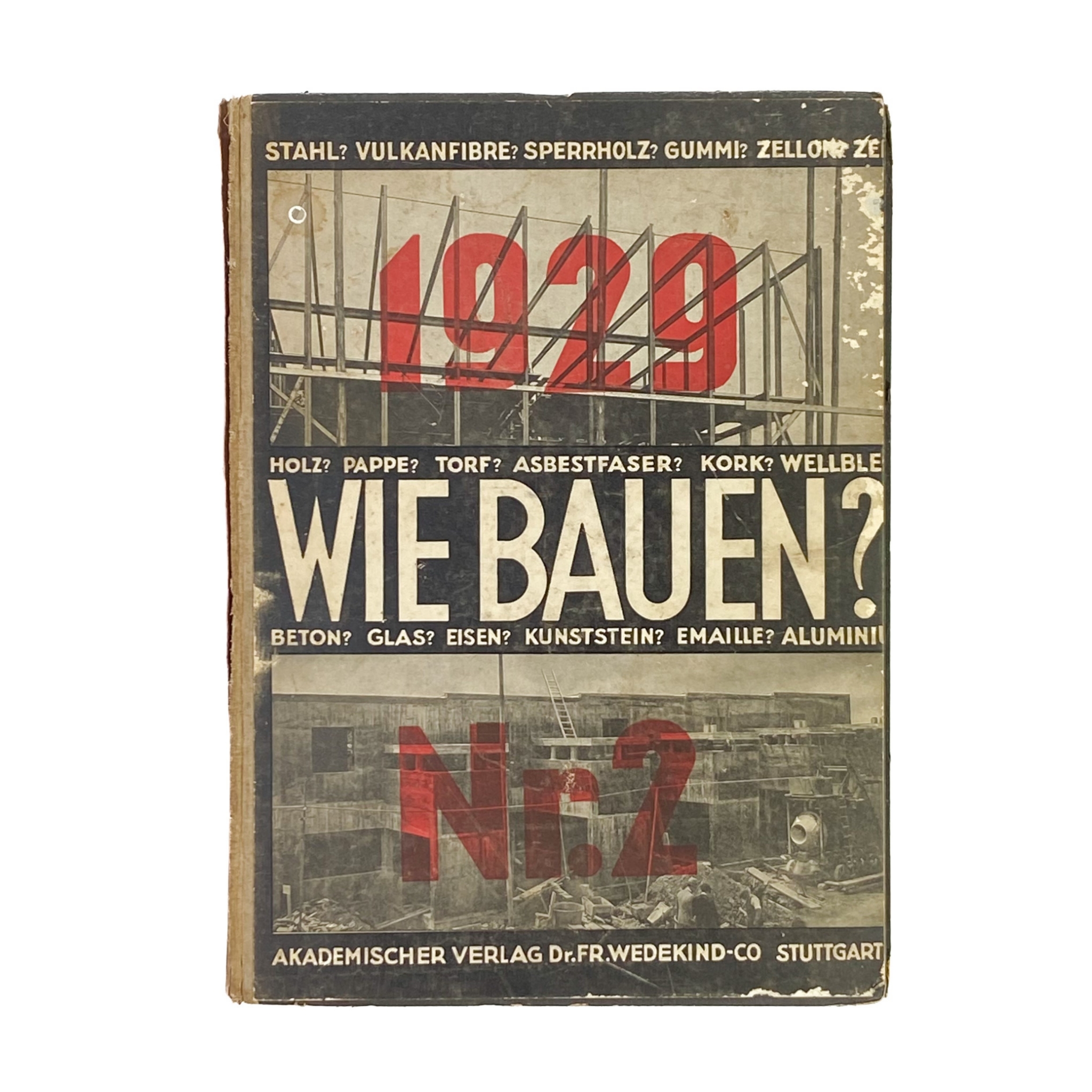

“Wie Bauen?» Was first published in 1927 in the context of the construction and interior design of the Werkbund estate at Weissenhof, Stuttgart. The volume is more than a superficial guide to the exhibition; it conveys the different approaches to construction in an entertaining and vivid way, initially distinguishing masonry structures from skeleton structures. Alongside details about the furnishings and construction of each of the buildings in the Weissenhof estate, a host of advertising clients presented details about the advantages of their products, from building materials to hot water supply systems.

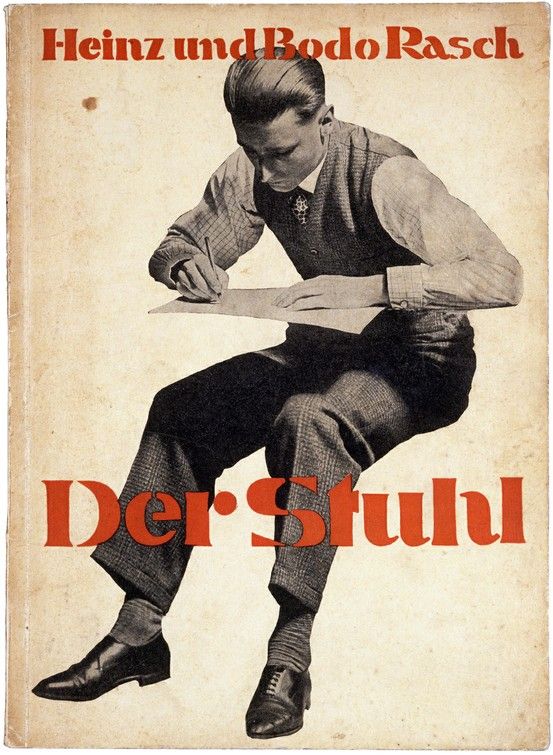

The Rasch brothers repeatedly and unabashedly inserted their own projects into the overall framework of the book.For example, it is in this book that they first present their most important visionary project, the idea of suspended houses. Furthermore, the furniture that the Rasch brothers designed for the Weissenhof houses of Mies van der Rohe and Behrens can be found in their publications. In 1928, a modified version, less laden with advertisements, dedicated to «materials and structures for industrial manufacturing» appeared. That same year, they wrote and designed Der Stuhl, just under 60 pages and reprinted in 1992 by the Vitra Design Museum.

In it, Heinz and Bodo Rasch (against alphabetical order, the name of the older of the two always appeared first) outlined the transition from craft to industrial production of furniture and, using examples of how they developed their own furniture as well as designs by Mart Stam and Mies van der Rohe, described how the structure of furniture changed due to new production methods and uses.In 1930, they published their systematic work Zu – Offen, which offered an overview of contemporary product types for doors and windows.

Gefesselter Blick was the name of their next volume, which contained 25 brief monographic texts on selected advertising designers, from Willi Baumeister to Piet Zwart, including Max Bill, Walter Dexel, John Heartfield, El Lissitzky, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Kurt Schwitters, Mart Stam, and Jan Tchichold. Here, the creators and designers Heinz and Bodo Rasch were also included, with programmatic statements, and it is only right that their names appear alongside those of designers who are much better known today. Heinz and Bodo Rasch fell out over copyright issues and stopped working together.

The reasons were not only the impact of the Great Depression but also changing life circumstances (both had married, Heinz in 1930, Bodo in 1931). They went their separate ways and only communicated by letter. Some of their designs, for example those for the innovative suspended houses, are in the collections of the Canadian Centre for Architecture in Toronto, the MoMA in New York, and the Deutsches Architekturmuseum in Frankfurt, which have loaned works to the Herford exhibition.