Andrea Leria

ARCHIVING THE SELF: ASHES, MEMORY AND TESTIMONY

INTERVIEW WITH CURATOR LUZ MUÑOZ PHOTOGRAPHY BY MICHELE MOREA

The Encounter

Luz. We first crossed paths in 2019 at a mutual friend’s exhibition in the city of Barcelona, an encounter swayed by a shared interest in archives. Andrea Leria, an artist whose practice may be explained through three conceptual pillars: the family archive, women’s genealogies, and identity. As a curator and researcher, I’ve spent over 20 years immersed in the research, reflection, preservation, and visibility of art archives.

Together, we’ve opened a Pandora’s box, embarking on a journey of more than 4 years of endless dialogues. From your studio, we’ve co-created projects that have challenged and enriched us mutually. Our ongoing journey together has translated into three solo exhibitions, publications, and two artistic mediation programs. These experiences have provided us with the opportunity to delve deeper into topics that raise questions about archives, identity construction, and memory. Could you tell us what were the catalysts for your creative process revolving around archives?

Andrea. There is in me a sense of estrangement, born from a life marked by displacements. The biographical is forever tangled with the unresolved notion of one’s rightful place and an ever-changing identity. I returned to live in Spain at the age of 34, only then I began reconnecting with my maternal family history after a prolonged period spent in Chile and England, where I spent my childhood, adolescence and early adulthood. I was born in Barcelona in 1980 where I lived until I was 6 years old. In those early years, I was the sole granddaughter of Montserrat Bores, my maternal grandmother. The reunion with her at the age of 34 marked a turning point in my life and my artistic work. In the next four years, we began a process of “family excavations” in her home. We opened drawers, chests, and closets, seeking to reimagine and reconstruct the landscape of my early years, searching for traces of a genealogical footprint amidst a geography lost to migrations and displacements.

In her apartment, we unearthed objects, photographs, and documents collecting fragments of my childhood memories, all while she—my grandmother—was losing hers. As we continued these excavations in her home, it became evident that the return to my childhood place and the encounter with the family archive marked my artistic explorations about memory and identity. From this experience, I began to wonder, “How does the past define us? How does memory inscribe itself in the archives that permeate our everyday lives? How can the construction of memory re-signify our lives? To me, an archive is a repository of meaning, a living entity, ready to be disseminated to discover new connections. The most significant aspect of any archive is its ambiguity, the infinite possibilities and interpretations that can emerge from it.

Capturing Memory through Images.

L. These initial excavations in Montserrat’s home open a doorway into your early years in Spain, a lost identity, a process of encoun- ters with memory and emotions during a sensitive time. While you construct the iden- tity of your early years, you bear witness to the progression of her illness. She is losing her memory, and four years after your return to your place of origin, she departs. From this moment on, you become the custodian of her family archive: notebooks, journals, correspondence, photographs, audiovisual records, and collections. An inheritance that has deeply impacted both you and your work. Returning to the questions you raise about memory and identity in relation to the archi- ve, could you expand into the subject of how memory inscribes itself in the archives that permeate our everyday lives, re-signifying our very existence?

A. In recent years, I have translated picto- rially, covered, assembled, crushed, and per- formed upon the surfaces of everything my grandmother collected during her 87 years of life. My artistic-investigative practice and fascination with archival material does not intend to problematize its accumulation, but to reinvent fragile and plastic forms that allow to dust off what appears to be dormant. Aiming to give meaning to our experience when we confront documents, objects, and photographs that witness our existence and journey through this world. Through my un- derstanding of archival material as a ducti- le entity that never quite concludes being, I want to shake up the archive, draw out its latent forces, to evoke more universal themes. In this regard, I would like to draw attention to “Boira” an exhibition at the MAMT Tarragona Museum in 2019, which marked a turning point in my journey through my family archive. “Boira” means “Fog” in Catalan, my native language that I do not speak.

This exhibition was initially intended to be constructed upon dialogues with my grandmother, but unfortunately, she passed away 9 months before the opening. The title refers to the heaviness I felt when I delved into the hundreds of remnants she left behind without her guidance. It was an overwhelming experience to embrace the potentiality of their multiple meanings, to think and delve into other ways of constructing memory through objects and documents. Boira and the various artworks that were a part of it, present to the viewer ’exercises in memory activation.’ They explore different ways of inhabiting our family archives and serve as an attempt to leave a mark, to record and archive what, in each of our lives, can hold significance.

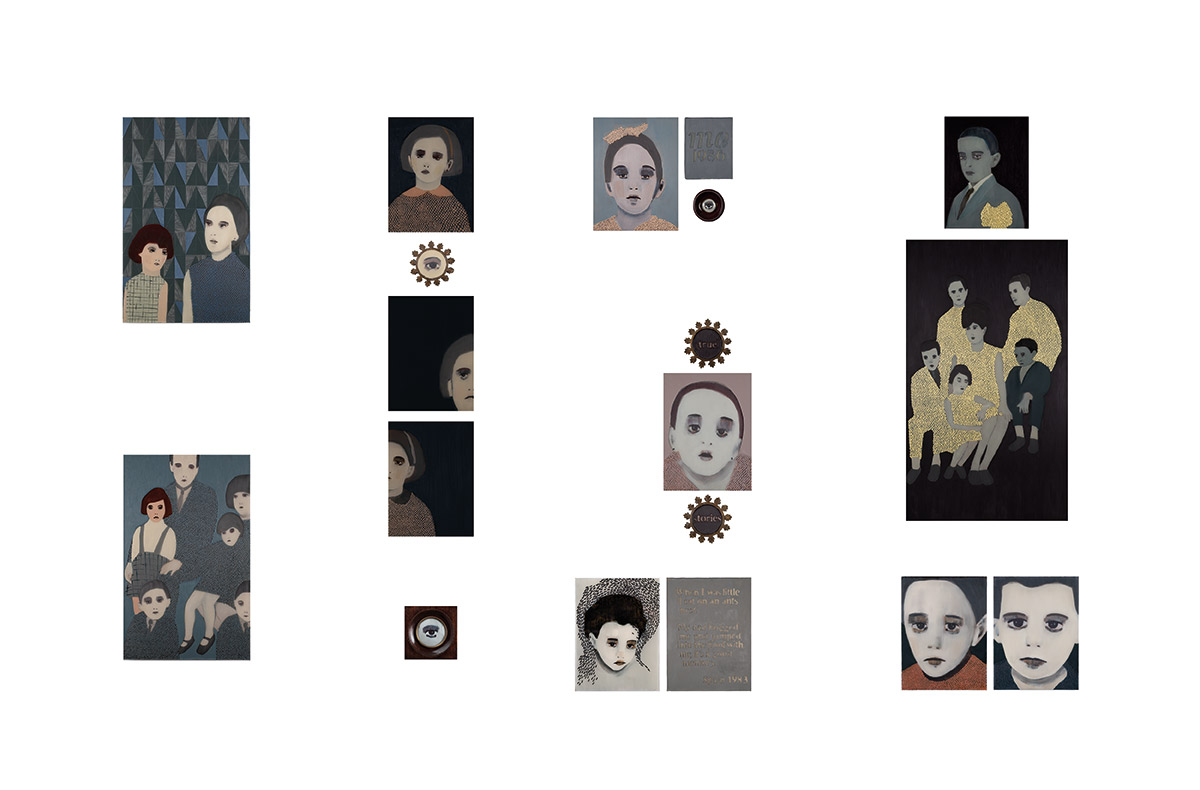

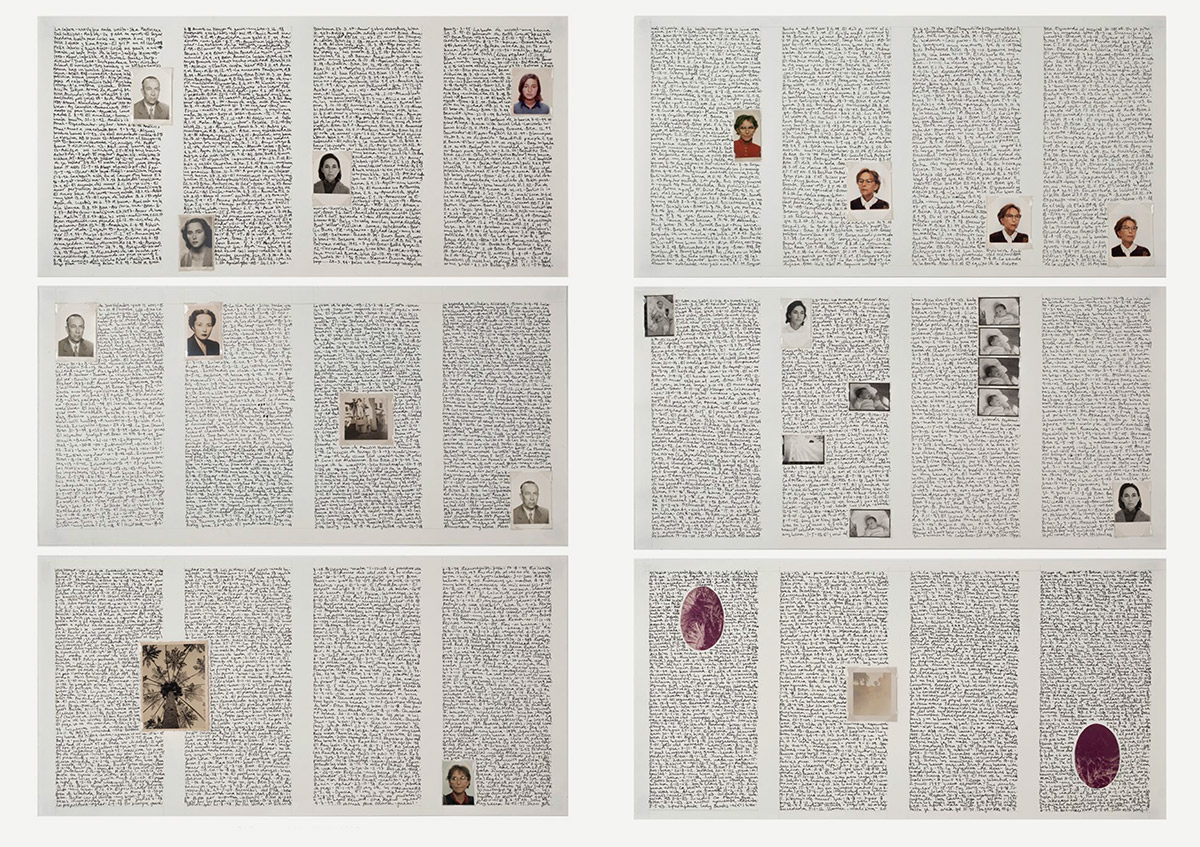

The result was a stage set that transports us, through the artworks, into a series of dialogues and reflections that take form through various mediums such as painting, writing, video, and raw archival material. The Shadow—public, private, and secret—a series of paintings created from passport and ID photos that I found in a small box. She had saved all her ID photos throughout her entire life. This large-format polyptych composes notes that mark the passage of a lifetime, juxtaposing the portrait with the concept of identity. Reliquary: 1986- 2025, an installation composed of 9 drawings, photographic images retrieved from the family archive, and her ‘film notebook.’ A handwritten text that directly transcribes the contents of the notebook—a list of hundreds of films she watched over 39 years, classified and categorized by dates.

The notebook is no longer accessible, and the performative act of transcribing it in my handwriting highlights the chronology and the journey she undertook in her life, with images as an escape route. Silenced, a video piece with no sound made of found footage Super 8 films I discovered inside a closet in her flat. Home movies she made during her travels around the world, Egypt, Paris, Switzerland, Afrika, etc.- between 1965 and 1978. The audiovisual piece, activated through an analog projector, opens interpretations of what was lived, what was narrated, and what was left unspoken.

From the Personal to the Universal

L. In your artworks and the investigative aspect that it carries, a duality exists. On one hand, there is the exercise of a performative act upon the archive, activating it and transposing it into a new context; moving from its materiality and original meaning towards an aesthetic, poetic, and political action. On the other hand, the archival material undergoes a change in status and aesthetic value through various strategies: intervening in it, translating it pictorially, or even fragmenting it—actions related to the archive that often led the initial document to its disappearance. Through these actions, archives travel and transform into works of art. In your exhibition setups, you construct a spectrum of narratives that weave discourses ranging from the most personal and intimate to universal issues. I would like to ask you, from your grandmother’s extensive archive, which stories have had a significant impact on your creative processes? Can you provide specific examples of works where you’ve managed to connect your personal archive with more universal issues?

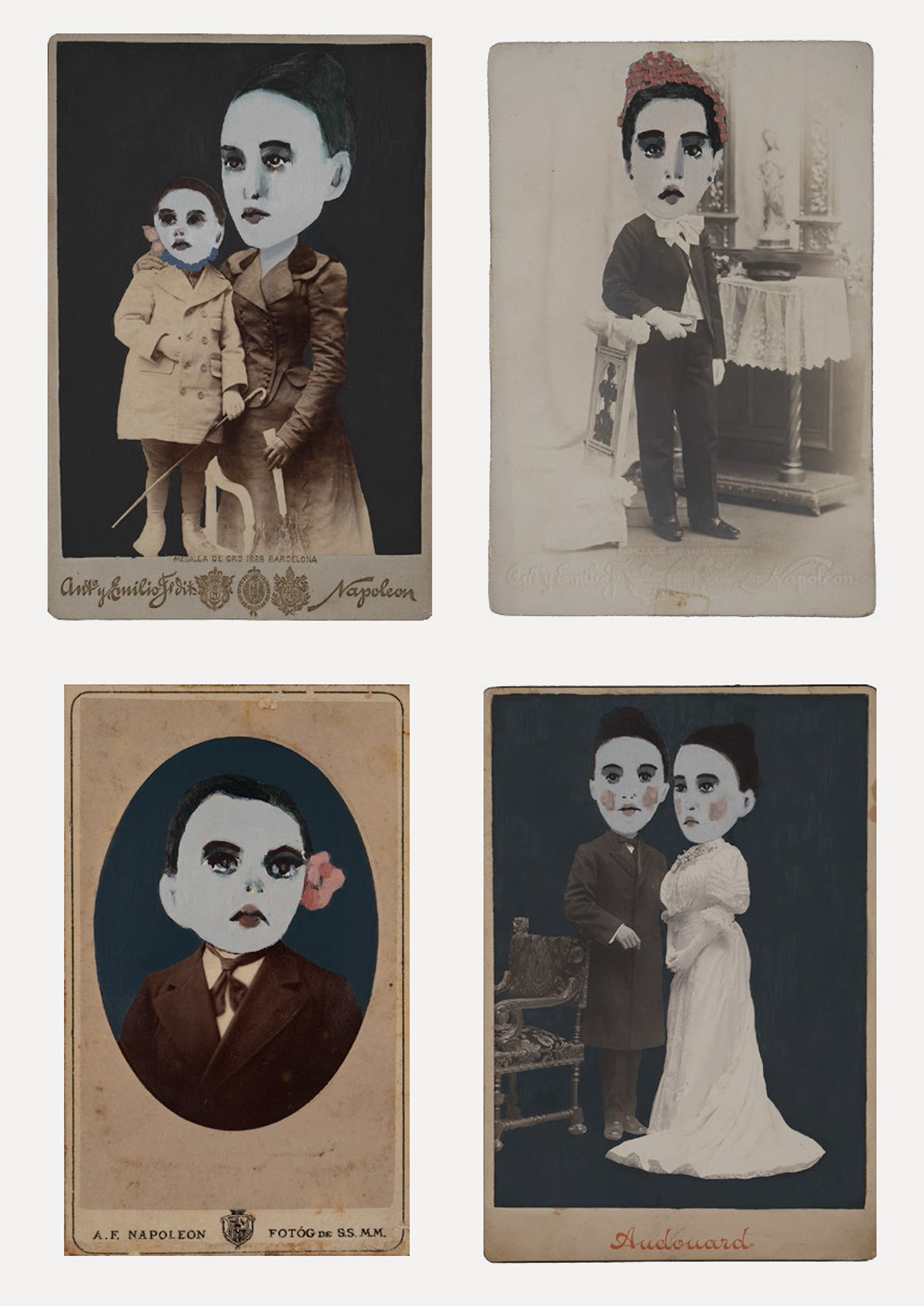

A. The work we undertook together with my grandmother flooded me with childhood memories. Gradually, my perspective on the past and its material remnants changed. In that gradual shift, I moved from merely observing the past – and by extension, my family archive – and understanding memory in a superficial and aesthetic sense to evaluating the past and the way we engage with it as a political act, as a way of inhabiting the world, as a complex process that shakes the foundations of both private and public histories. My “family excavations,” which are nothing more than a way to make sense of my existence, prompted me to think of the family archive – and by extension, any archive – as contested spaces where history is revisited through the destruction and re-signification of its elements. Montserrat Borés was born in the early thirties, the daughter of a Catalan bourgeois family of the time. Her destiny, after a brief stint at a finishing school in Paris, was expected to involve marriage and dedicating her life to her family, in a society that imposed a traditional and subordinate role on women.

A spirited woman ahead of her time, she didn’t confine herself to the roles of a wife and mother; instead, she sets off to explore the world. Two years after her passing, one night in my studio, as I was going through a box containing her documents and notebooks, I discovered a letter she had written inside an old book. This document was the catalyst for a series of works that culminated in an exhibition titled “Gardens of Resistance,” which traveled to Chile in 2021. This exhibition traced a line of female genealogies, with their own timelines and narratives. It resurrects lost and marginalized memories within the vicissitudes of history, culture, and the idiosyncrasies of a patriarchal society. It’s a journey through the inner landscapes of the feminine universe, worlds shaped by the places they’ve had to inhabit, generation after generation. It’s an attempt to break free from the conditioning to which we are subjected simply by being born in a specific place, into a particular family with its circumstances, customs, and beliefs that, consciously or unconsciously, predispose you to be something you’re not.

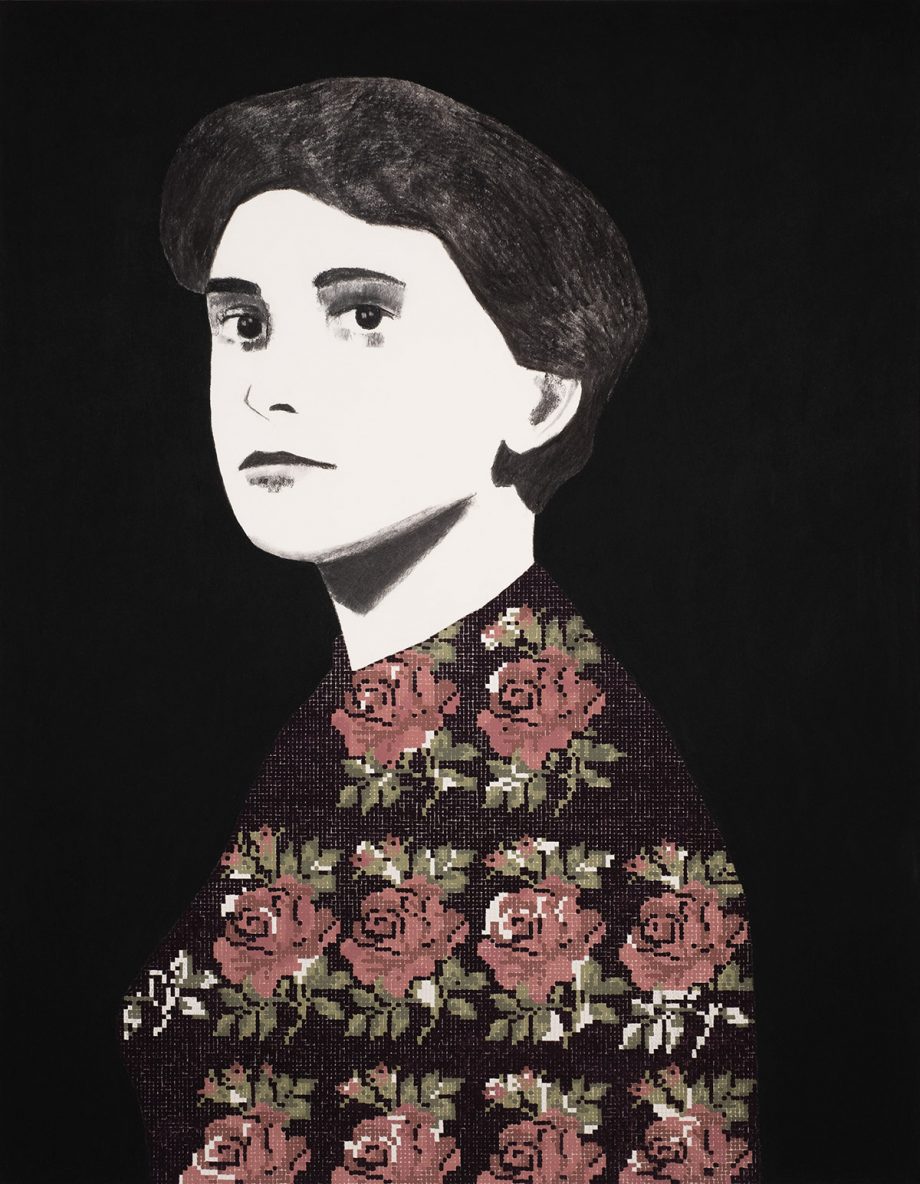

Based on the above, I would like to discuss two works that originated from the letter I discovered, and I am certain, due to its content, was written with the intention that it should never be read by anyone. My emotional connection to the material made it impossible for me to fetishize it and reveal family secrets. There- fore, in the midst of the pandemic, when I was confined to my apartment in Barcelona, I made the decision to meticulously cut it into pieces along with the book that concealed it. The result is a series of patterns and folds created from the destroyed archive, obses- sively covering parts of a portrait I drew of her, based on an old photograph. This work delineates its boundaries within an ‘archive garden,’ stemming from the relationship be- tween the action (destroying the documents) and the artwork (drawing). This piece bears the same title as the exhibition: “Gardens of Resistance: Last Breath.”

“Testimony” is the title of the second work that is activated from the letter I shredded. A phrase drawn from my grandmother’s own handwritten writing, replicated in a neon pink light sculpture reads: “I cannot love an- yone.” It pierces me like lightning, questio- ning the ways in which we understand wo- men’s roles in the family. In both “Gardens of Resistance: Last Breath” and “Testimony” I explore my personal history and, in doing so, indirectly examine the collective history of many women.

L. In both “Boira” and “Gardens of Resistance” you’ve explored the realm of the feminine through the traces left by your grandmother, challenging the institutional practices of archiving. I’d like to focus on two large- scale portraits that were part of “Gardens of Resistance”—your image and hers in communion— that originatated from the act of drawing and recovering patterns from her crochet magazines. On more than one occasion, you’ve referred to these pieces as ‘performative drawings,’ a term connected to the process of creating these portraits. Could you elaborate on this process and how it connects with memory and the female universe?

A. I remember my grandmother crocheting; I have this image of her carved in my memory since I was a child. In my home, I treasure the towels, curtains, tablecloths, placemats, and cases she knitted. Emptying her house was a daunting task; she kept everything: folders, envelopes, boxes, cases, correspondence, diaries, phone books, photographs, postcards, envelopes from every hotel she visited around the world, hundreds of miniatures of priests and nuns, just to name a few. By not adhering to the traditional criteria pursued by archival science in the formation of her deposits, her archives and collections rather reveal the collector’s passion. One of the collections recovered from a wardrobe, is her collection of crochet magazines.

This collection and the image of her sitting in her armchair, knitting, serve as the catalyst for two large-format drawings: ‘Weaver of Shadows’ and ‘In My Own Words.’ These two pieces constitute a performative action that is realized through a drawing as a starting point with the translations of colors and patterns from her crochet magazines. During the lengthy process of creating these works, even though she wasn’t with me, I was drawing, and she was knitting. These drawings travel through the past and the present, our existences converge in the act of drawing and translating her archive. In the internal, emotional, and creative journey I undertake to shape the exhibition setup “Gardens of Resistance,” the house, the family, the affections, the intimate ways of dwelling, desires, secrets, and resistance to imposed norms are un- veiled. Transforming personal experien- ces and archives into artistic and evo- cative devices that blur the boundary between the private and the public, be- tween the lived and the evoked, between what is spoken and what remains unsaid.